The following article was prepared for a presentation to the Retirees of West Allis, Wisconsin, on Veterans Day 2011. The story of Milwaukee’s first Soldiers’ Home is told through the experiences of Fanny Burling Buttrick, one of the members of the 1862 West Side Soldiers’ Aid Society and, later, one of the Home’s Lady Managers.

See also our annotated West Side S.A.S. Chronology, featuring Minutes of the Wisconsin Soldiers’ Home Association, and the March 15, 2013, blog on Preservation Nation. Or connect with the modern-day West Side Soldiers Aid Society.

FANNY BURLING BUTTRICK & WISCONSIN’S FIRST SOLDIERS’ HOME

Early Relief Efforts / Refocusing the Mission / 1864 Memphis Campaign

Forest Home Cemetery / National Efforts / Plans for a Wisconsin Home / Links Fanny Burling was born in New York City and educated at Leroy Female Seminary near Rochester, New York—one of the first institutions to offer a college preparation program for young women. Finishing her studies, she moved with her family to Wisconsin where she was known as the Belle of Green Lake. On Christmas Day 1851 she married Edwin Lorenzo Buttrick, an attorney from Oshkosh. The Buttricks moved to Milwaukee in 1852 after the death of their only child.

Early Relief Efforts At the outbreak of hostilities in 1861, Fanny joined with the young ladies on the West Side of the Wisconsin river to produce or collect whatever troops required: warm winter clothing, quilts, prepared foods and medicines, bandages, newspapers.

Refocusing the Mission By the spring of 1864 the Society felt that soldiers passing through the city or returning from battle needed as much if not more attention than those on the front. The West Side Soldiers Aid Society dissolved its relationship with the Wisconsin Soldiers’ Aid Society (an auxiliary of the United States Sanitary Commission) and reorganized as the Soldiers’ Home at Milwaukee, renting storefronts on West Water Street (now Plankinton) north of Spring Street (now Wisconsin). They emphasized that their Home was “Not an alms house but a home where our brave boys shall receive at our hands some faint return for the benefits their valor and patriotism have won for us and our beloved country.” Within days of opening, the Home was inundated with 100 residents, some passing through, some in need of medical care, food, clothing.

The Milwaukee Sentinel carried detailed reports of individual contributions to Home, the ladies’ creative fundraising activities, and a list of all admissions by name, state and regiment.

From Battlefield to Soldiers’ Home

Fanny learned first-hand about the horrors of war and the suffering of Union soldiers when she accompanied her husband Col. Edwin Lorenzo Buttrick and Wisconsin’s 100 days regiments to the front at Memphis, Tennessee, in the summer of 1864. It was all she could talk about for years to come. Some of her experiences are recorded in her letters to the President of the Soldiers’ Home, her friend Lydia Docenia Ely Hewitt. In her first letter she reports the first deaths of her boys, including the death of Frank Burlingame of Ripon. Measles, typhoid fever, dystentery took their toll.

On August 21, 1864, the hundred days men saw their only major action: a dramatic morning raid into Memphis by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest’s cavalry troopers were known for their savageism. The Memphis Bulletin reported that during this raid those troopers made an assault on the Hospital of the 137th Illinois, where three invalids unable to rise from their cots were shot in the head and bayonetted.

Fanny writes: “You have doubtless heard about the great raid into Memphis? Our boys did not see all of it — that they wanted to, but I felt that they had seen enough when I looked upon the stiffened bodies of three as they were taken from the ambulance and heard the groans of the wounded of other regiments who were brought to our hospital. As soon as it was broad day light, I went over to the camp and cooked breakfast for headquarters with the cannon roaring in my ears and the balls flying overhead. It was grand. I enjoyed it ever so much. I wish you were here.” By the end of the 100 days, eighteen boys had died, including Charlie Mooers, a drummer boy from Milwaukee. On September 8, 1864, she warned her friends at the Soldiers’ Home that the trains were loaded with the sick — as many as 60 from the 39th Wisconsin alone.

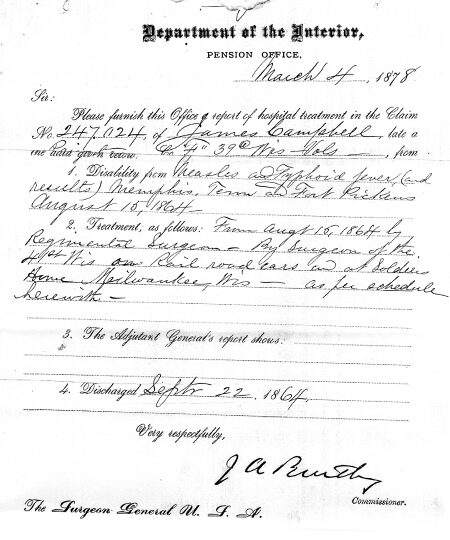

Above: James Campbell, one of the 100 Days Men admitted to the Soldiers’ Home On September 19, an appeal was published in the Milwaukee Sentinel: “To the friends of the sick at the Soldiers’ Home — There is an urgent call for suitable provisions, ready prepared for the sick. They must be sent in immediately, as there are about 100 sick to be cared for. By order of the President, Saturday, Sept. 17th.”

Reverence and Remembrance

Sadly, in the Home’s First Annual Report to the State of Wisconsin, 7 from the 39th are listed among those who died at the Home between September 19 and 29, 1864. The report states that “Whenever possible, the ladies paid for funeral expenses and forwarded the remains to the homes of the deceased. When friendless, the ladies have stood by them, until the last whisper had ceased, as by those to whom they owed a debt which no human tongue could tell. They were borne to honored graves in our beautiful ‘Forest Home’ [Cemetery] — followed to the last by some of the ladies.”

National Response On March 3, 1865, after a lengthy debate on the need for veteran care, President Lincoln signed “an Act to incorporate a national military and naval asylum for the relief of the volunteer forces of the U.S.” On the following day, he delivered his second inaugural address, including the phrase which continues to animate care for our nation’s veterans: “to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphans….”

A Permanent Home for Wisconsin’s Volunteers A Constitution and Bylaws of the Wisconsin Soldiers’ Home were approved in April 1865 and signed by Governor James Lewis. Along with a charter and a $5,000 grant, the women received the go-ahead for a great State-wide fundraising fair to build a permanent Home in Milwaukee.

The following declaration appeared in the First Annual Report for the year ending April 15, 1865.

This HOME is not a wayside charity, or transient recreation, but a serious and permanent assumption of a sacred duty which we owe the defenders of our common country. It is food for the hungry, comfort for the cheerless, sympathy for the afflicted. It is a constant acknowledgment, that we too have duties, personal and direct, connected with the conflict that convulses our country, which can neither be postponed or evaded. It is an embodied declaration, that we at home acknowledge our obligations and are willing to share with them the arduous responsibilities of the hour.

The fair of June-July 1865 was a huge success in raising funds, in providing food and lodging for soldiers, in entertaining the public and returning a sense of normalcy. The 10-day fair had an extended run, amassing $110,000 for the Wisconsin Soldiers’ Home.

Soldiers’ Home Fair Building courtesy of Zablocki VA Medical Center Archives

Local, state and national politics won the day, however, when the ladies were persuaded to turn over their assets to establish the Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. By 1867, according to some reports, the women had given aid to 31,000 soldiers. Annual Report Wisconsin Soldiers Home: during year ending April 15, 1865, 4,842 had been received by the Home. The ladies’ stipulations to the federal government included one small phrase that, we believe, makes Milwaukee the “Mother” home of the national home system: they insisted that the doors of the home be open to veterans of ALL wars, not just those who had served in the Civil War. On Veterans Day and every day, we honor not only those who have served our country in the armed forces, but also those who cared for them upon their return. What the women wrote in 1865 holds true today: “We, too, have duties, personal and direct…we acknowledge our obligations and are willing to share the arduous responsibilities of the hour.” Patricia A. Lynch

Read more about the West Side Soldiers Aid Society here and on the Preservation Nation Blog. And learn about the present-day West Side S.A.S. here. This website is part of the Society’s mission to history, veterans, and the Zablocki VA Medical Center.